Grip Test Helps to Identify and Monitor Fragile X Tremor-Ataxia Syndrome in Adults, Study Suggests

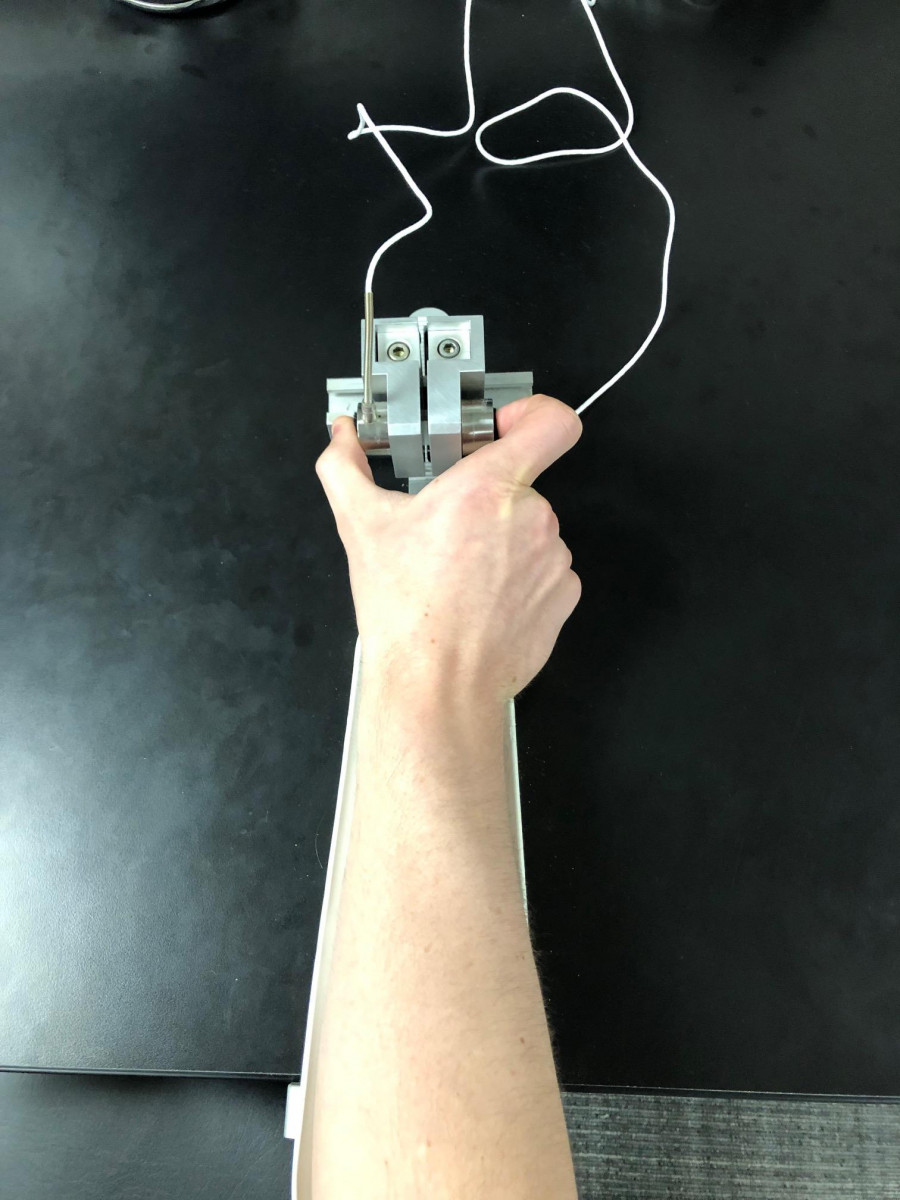

Grip test courtesy of the University of Kansas.

Precision grip tests could help doctors to identify and monitor fragile X-associated tremor-ataxia syndrome (FXTAS), a common condition in families affected by fragile X syndrome, a study reports.

Subtle alterations in motor abilities are seen as a normal part of aging, but some changes like hand tremors may be an early indication of FXTAS onset, researchers say.

The findings, “Precision Sensorimotor Control in Aging FMR1 Gene Premutation Carriers,” were published in the journal Frontiers in Integrative Neurosciences.

FXTAS is a neurodegenerative condition characterized by ataxia, or progressive movement abnormalities, and tremors (rhythmic, involuntary movements) that start in adulthood and predominantly affect men.

Individuals with this condition have a “premutation” in the FMR1 gene, consisting of 55-200 CGG repeats. In turn, fragile X patients have “full” (longer) mutations in FMR1, with over 200 CGG repeats. (Of note, C stands for cytosine and G for guanine, two of the four building blocks of DNA.)

Although premutation carriers are at risk of developing FXTAS, no method now exists for predicting who will end up developing the disorder. Diagnosis of FXTAS can be difficult because its neurological symptoms are similar to other late adult-onset disorders, such as Parkinson’s or Alzheimer’s.

“What will happen is there’s a kinetic tremor, a shaking of the hands, as these folks try to reach for objects or try to do some sort of coordinated action,” Walker McKinney, the study’s lead author at University of Kansas (KU), said in a news story by Brendan M. Lynch.

“Some also have problems with walking and balance. On top of that, some have significant cognitive difficulties and psychiatric symptoms. So, they’re at risk for higher rates of depression, anxiety, and cognitive decline,” added McKinney, who performed the research at KU’s BRAIN Lab.

Finding ways of quantifying early symptoms of FXTAS could provide insights into its underlying neurodegenerative processes and help predict who may develop FXTAS.

A research team with the university’s Life Span Institute developed a precision grip-force test to quantify sensorimotor function — here, roughly meaning hand-eye coordination — in 26 people with FMR1 permutations (ages 44 to 77) and 31 healthy individuals. Researchers compared the two groups to determine the risk and severity of FXTAS.

“We were interested in looking at really quantifiable, really precise measurements of their behavior — to see if people who didn’t think they had the disease were maybe showing some symptoms of early decline that wouldn’t have been detectable by neurologists or by their doctor, or even noticed by themselves. So, we recruited people who really didn’t think anything was wrong with them,” McKinney said.

Each participant was asked to manipulate bars on a video screen by squeezing a device — a custom-made arm brace and load cells — during tasks that were rapid (2 seconds) and sustained (8 seconds), and at multiple force levels. The researchers then measured speed and accuracy.

Results showed that premutation carriers were slower to start pressing and to increase their force once they pressed. Evaluation of how well they could maintain a steady grip also found difficulties in precisely and rapidly adjusting their force when the bars moved apart.

Greater motor problems were associated with the longer CGG repeats and more severe FXTAS symptoms, suggesting that they could indicate who will or already is developing the disease, the researchers said.

Carriers of longer repeat lengths “had the less-complex signal, which is more characteristic of a tremor — perhaps even a detectable sub-clinical tremor the participant isn’t even aware of yet,” McKinney said.

“None of them had been identified as having FXTAS, and none of them reported having any concerns — they just assumed changes in their motor abilities were part of normal aging. But then, as we sat them down and did this laboratory testing, and measured their precise motor behavior, some of them were actually showing detectable and significant motor deficits,” he added.

Overall, the findings suggest that tests of precision sensorimotor ability “may serve as key targets for monitoring FXTAS risk and progression,” the team wrote.