Israeli Clinic for Fragile X, One of World’s Largest, Adapting with COVID-19

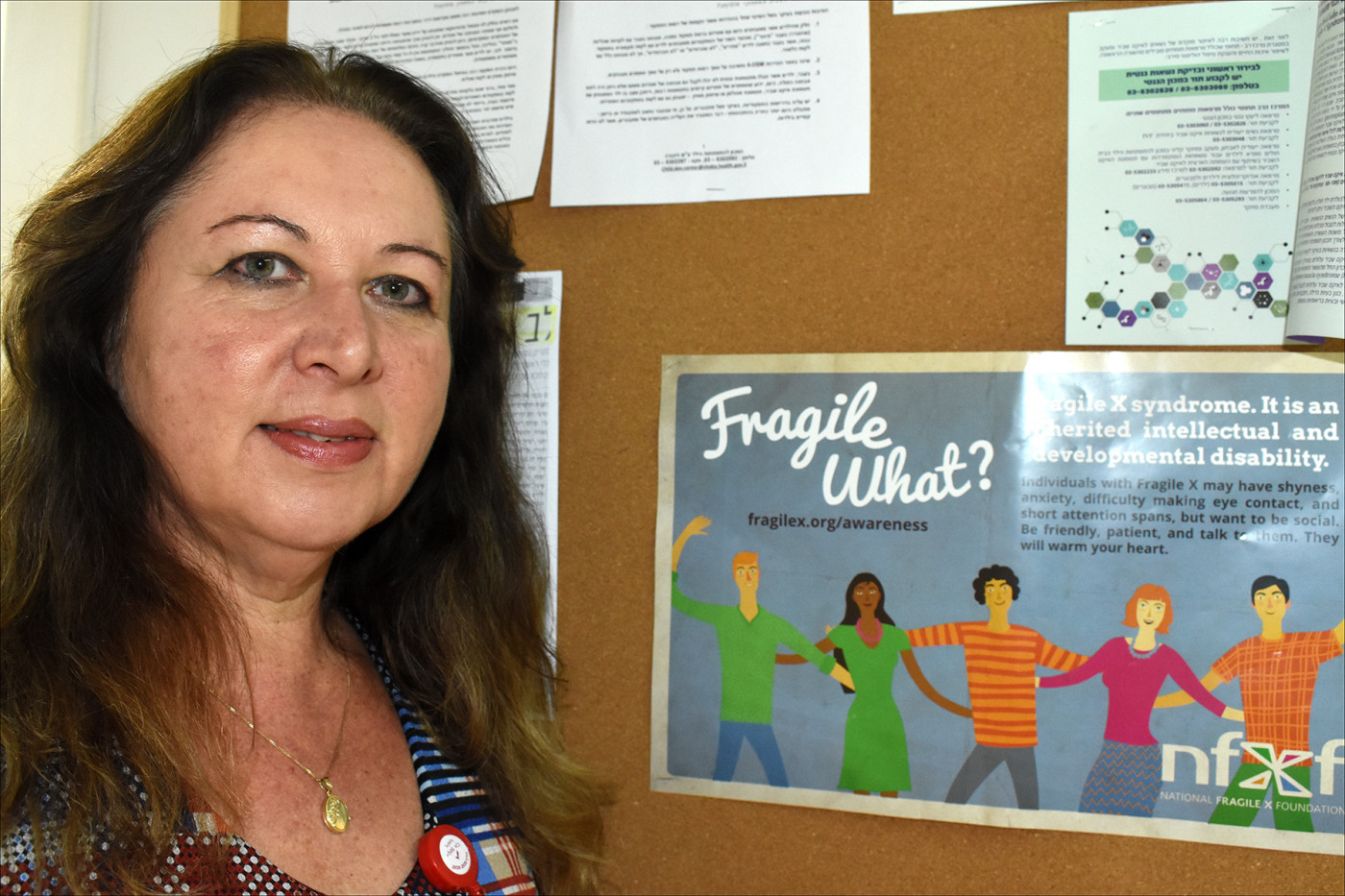

Lidia Gabis, MD, director of the Keshet Center for Autism and one of Israel’s top experts on fragile X syndrome. (Photos by Larry Luxner)

Caring for kids with fragile X syndrome — the most common inherited cause of intellectual disability — is challenging even under normal circumstances. Now, as the worst pandemic in more than 100 years sweeps the planet, those difficulties are compounded many times over, says Lidia V. Gabis, MD.

Gabis is founder and director of the Keshet Center for Autism, a unit of the Sheba Medical Center at Tel Hashomer and Israel’s top institution dealing with complex developmental disorders. She said the current nationwide lockdown prompted by COVID-19’s spread throughout the Jewish state has forced the center to put many of its programs online.

“Although Israel’s population is relatively small — about 9.1 million — our clinic is one of the largest of its kind in the world because the prevalence of fragile X in Israel is so high,” the pediatric neurologist told Bionews Services, publisher of this site.

The Keshet Center, established in 2006 and located in the Tel Aviv suburb of Ramat Gan, focuses on specific genetic disorders related to autism. It employs 130 professionals such as psychologists, social workers, researchers and speech, occupational and physical therapists.

Roughly 20 focus specifically on fragile X, with the center treats about 300 of these patients on a regular basis.

“Since 2013, screening for fragile X is free for all childbearing women in Israel,” Gabis said. “Any woman can get carrier testing. Since Israel is one of the few countries that offers this, we’ve started to see that in some ethnic populations, the disease is more common than in others.”

In Israel, about 1 in 140 people are carriers, compared to 1 in 250 in the United States. But in certain specific populations within Israel itself, the prevalence is much higher. For example, 1 in 40 Sephardic Jewish women descended from the Tunisian island of Djerba carry the fragile X-causing mutation.

The disease is also relatively common among Moroccan and Iraqi Jews, as well as among Ashkenazi Jews from northern and central Europe — particularly Scandinavia, Germany, and Britain.

Screening of vital importance

Gabis estimates that Israel is home to roughly 7,000 to 8,000 people with fragile X, making it 100 times more common than Angelman syndrome. Some 80% of Israeli women are screened for the disease; the remaining 20% are from ultra-Orthodox Jewish or Arab Muslim families whose cultures frown on such testing.

“We try to emphasize that it’s important for all women to be screened,” she said. “When we have a Tunisian family, we sometimes screen both parents, and if they did the test long ago, we sometimes repeat it. We do everything in our power to increase awareness.”

Gabis earned her medical degree from Jerusalem’s Hebrew University-Hadassah Medical School as well as an MBA from Israel’s Collman Business College. She trained in pediatrics at Kaplan Hospital — also in Israel — and later did a fellowship in pediatric neurology at State University of New York-Stony Brook. For nearly 15 years, she has directed the Keshet Center as well as its Fragile X Resource Center and Clinic.

Gabis said people with genetic forms of intellectual disability who don’t have Down syndrome frequently have fragile X, though the disorder is often not diagnosed properly.

“Fragile X should be considered in every child with some sort of developmental delay,” she said. “It can present with motor delay, or with communications or language problems. We try to guide primary-care doctors not to rely on physical features [such as a long and narrow face, large ears, a prominent jaw and forehead, unusually flexible fingers, flat feet, and in males, enlarged testicles after puberty] since many kids don’t have any of the physical features of fragile X.”

The disease itself is caused by genetic abnormalities in the FMR1 gene, which is located on the X chromosome. People with 54 or fewer repetitive sequences, known as CGG repeats, are considered normal, while those with 55 to 199 repeats (known as premutation) are carriers. Those with 200 or more such repeats have fragile X.

“If a mother with 55 to 199 repeats passes it to her son, this number will expand and the boy may have more than 200, and the full syndrome,” Gabis said, adding that all boys and half the girls with the full mutation have developmental disability.

“That’s the main reason women are screened, in order to advise them how to prevent having a child with fragile X. In a known carrier of the pre-mutation, there’s still a 50% chance of transmitting a non-carrier X chromosome, so a pre-implantation diagnosis — a type of in vitro fertilization — can be performed in which the embryo is returned only if it doesn’t carry fragile X.”

Bringing clinical trials to Israel

Gabis said it’s important to screen women not only for their potential of having a child with fragile X, but also because of the possibility of premature ovarian insufficiency (POI). This means they may become infertile at a relatively young age. POI is considered one of the main causes of infertility.

“One patient was only 19, though most are in their early 30s,” she said. “Often, those parents of children with disabilities may postpone parenthood, and also for many other reasons, so the knowledge of the predisposition may influence family planning.”

Gabis is honorary president of the Israeli Fragile X Parents Association, which has about 300 member families. One of the group’s objectives is to attract more clinical research to Israel.

“The main reason scientists became interested and parents became more hopeful is that about eight years ago, research started to emerge that aims to change the disorder, not just treat the symptoms,” she said. “It was extremely difficult to bring those studies to Israel, but since this disorder is so prevalent in Israel, we have succeeded in convincing a few drug companies to do clinical studies here.”

In fact, the Keshet Center has participated in clinical trials for Novartis and Israel’s Alcobra (which has since merged with Arcturus Therapeutics) regarding potential therapies for fragile X. While neither effort yielded positive results, all eyes are now on OV101 (gaboxadol), a once-a-day pill being developed by New York-based Ovid Therapeutics for both fragile X and Angelman patients.

Coping with coronavirus lockdown

With coronavirus on the rampage, Israel is now under a near-total lockdown. As of March 31, nearly 5,000 Israelis have been infected, and 16 have died, with those numbers increasing. All schools are shut, public gatherings of more than 10 people are banned, and Israelis are generally prohibited from straying more than 100 meters (about 328 feet) from their residences — unless they’re buying groceries or medicine, or they’re essential workers on their way to or from their jobs.

All this has made it particularly hard for families affected by fragile X.

“The educational system is now closed, so special-needs kids are at home. For the past two weeks, we’ve been treating everybody remotely,” Gabis said. “The clinic is still open, but many people are afraid of coming. It’s a huge challenge.”

To the extent possible, Gabis and her staff are treating the kids via telemedicine, with parents receiving online guidance and individually designed videos on how to exercise at home — and how to administer physical therapy. The Keshet team is now providing online parent groups and support from dawn to nearly midnight.

“It’s much harder for a kid with fragile X to stay home. They’re usually in an all-day school, and a change in routine is extremely complicated. Many of their parents have lost their jobs, and they have other children to take care of,” said Gabis.

On the plus side, most parents of children with fragile X have been able to obtain permits allowing them to take their children for walks beyond the 100-meter limit.

“We’re trying to help families establish new routines and not be in pajamas in front of the TV all day long,” she added. “We’re trying to structure their routines and organize their day. Many parents are starting to see more disability in their kids as a result of the situation, but some parents have also gotten more involved and have begun to see benefits.”